Four Hours At The Louvre Museum

The Louvre is the largest museum of art and antiquities in the world, as well as the most visited (with more than 10 million visitors per year). Anyone can recognize it just by taking a glance at its unique architecture—which blends Renaissance, classical and neo-classical styles—but also by the spectacular glass pyramid in the centre of its courtyard. The museum exhibits more than five hundred and fifty-five thousand works, including immensely famous creations like Vinci’s Portrait of Mona Lisa or the Venus de Milo. To fully understand the phenomenal quantity of pieces kept in the Louvre, one must know that if a visitor were to devote only ten seconds to each work, it would take him four full days to see them all. . .

In reality, visitors only spend a few hours in the museum. Which is why it is necessary to choose the right route in order to admire the must-see works—just after those mentioned above—for which it is better to be patient in order to even catch a glimpse of some of them due to the. Well then, follow the guide, and let us start this short tour of the Louvre with ten famous works of art not to be missed.

First, one has to climb the grand staircase and pass in front of the Winged Victory of Samothrace, and then continue on their way to stop in front of the painting of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (Leonardo da Vinci) or The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds (Georges de la Tour). The next step is to make an essential detour to the gallery that houses The Coronation of Napoleon (Jacques-Louis David), The Raft of the Medusa (Theodore Géricault) and the Liberty Guiding the People (Eugène Delacroix). Finally, finish this first stroll through the museum by passing through the square courtyard, and admire the statues exhibited in this vast and luminous room. So many infinitely famous works that one could tirelessly admire for all eternity. However, the Louvre also abounds in many other treasures, a bit more discreet, a little more hidden, but just as remarkable and admirable. The visit resumes, this time with a selection of lesser-known creations, to be discovered or rediscovered an infinite number of times.

FEMALE FIGURES

THE GRANDE ODALISQUE

A painter’s secret

Jean-Auguste-Dominique INGRES (1780 – 1867)

Denon Wing – Room 702

Ingres’ work, from the painting department, is installed in the Denon wing. From the very first glance, this harem woman transports us to a sensual vision of Orient. With her face turned towards the viewer, she represents a most fascinating, mythology-inspired nude. The contrast between the lascivious pose and the delicate economy of colours makes this painting a subtle and harmonious representation. However, the work was violently criticized when it was exhibited at the Salon of 1819: Ingres’ style was misunderstood and he was reproached for his disregard of anatomical accuracy. In fact, the painter added a few vertebrae to the young woman’s back, thus making it much longer. But who could deny the sensuality that this freedom from the artist gave the odalisque?

THE WOMAN WITH THE PEARL

The other Mona Lisa

Camille COROT (1796 – 1875)

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot succeeded in combining several immensely famous painters in this work. The title evokes another young woman, that of Vermeer, but the pose reminds us of Da Vinci’s Portrait of Mona Lisa. The clothes, the colours and the round face all remind us of Raphael’s paintings. The model, Berthe Goldschmidt, wears a very light veil on her head and a dress from Italy, brought back from a trip Corot himself went on. What was long thought to be a pearl is in fact a small leaf that delicately stands out on the girl’s forehead.

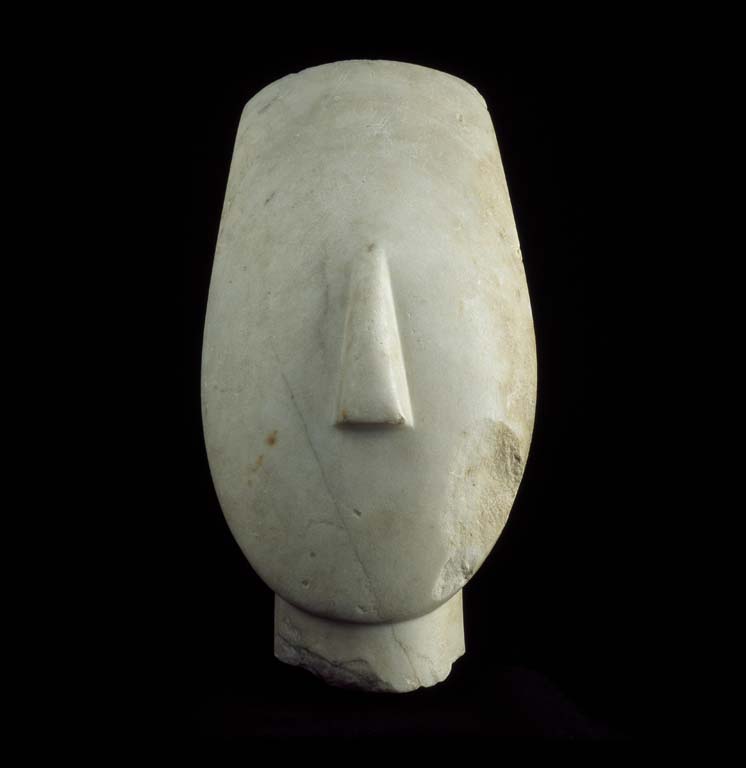

THE HEAD OF A FEMALE FIGURE

Picture-perfect face

Ancient Cycladic II (2700 – 2300 B.C)

Denon Wing – Room 170

This piece of great geometric purity is the first testimony of Greek marble sculpture. The exceptional size of the head (27 cm), along with the classical dimensions of a face, indicates that it probably belonged to the body of a naked female idol measuring 1.5 m. The balance of the composition is fascinating: only the ears (invisible from the front) and the nose are in relief. The shiny whiteness of the marble actually conceals an earlier polychromy, but gives this fragment of statue a soothing calm aura. This abstract aspect of the face has seduced and inspired the greatest modern artists, Modigliani and Picasso in particular.

MALE FIGURES

FRIEZE OF ARCHERS

The Immortals

Achaemenid Period – Reign of Darius 1st (around 510 B.C)

Suse – Darius 1st palace

Sully Wing—Room 307

King Darius’ guard always comprised of ten thousand soldiers, not one more, and not one less. Should one of them get sick or killed, he was immediately replaced. Herodotus nicknamed them the “Immortals”, for these men symbolized the grandiloquence of the Persian royal system. This wall housed in the Louvre depicts them in a colourful brick decoration inspired by the ones that adorned the palaces of Babylon. Here is the archers’ parade, armed with bows and quivers, and dressed in a large Persian dress. Their hairstyle was extremely intricate: thick brown curls were held by a diadem of admirable foliage. The frieze, which was originally very incomplete, has been admirably reconstructed by the restorers of the Louvre Museum.

THE HEAD OF THE RAMPIN RIDER

A soldier’s smile

Acropolis of Athens

Denon wing

While this head belongs to a horseman, another one, identical, was located on the exact opposite side of the Acropolis in Athens. His identity is uncertain, but such a duet necessarily brings to mind the twin gods Castor and Pollux, who watched over the Acropolis. The representation of the face is an incredible masterpiece: protruding cheekbones, pointed chin, almond-shaped eyes. The thickness of the pearls braided into the hairpiece, the curly strands of hair and the light beard all demonstrate a great decorative richness. The addition of a remnant reddish colour confers a diffuse charm to this work. In the end, the statue is sublimated by a rare and magnificent feature: a soft smile.

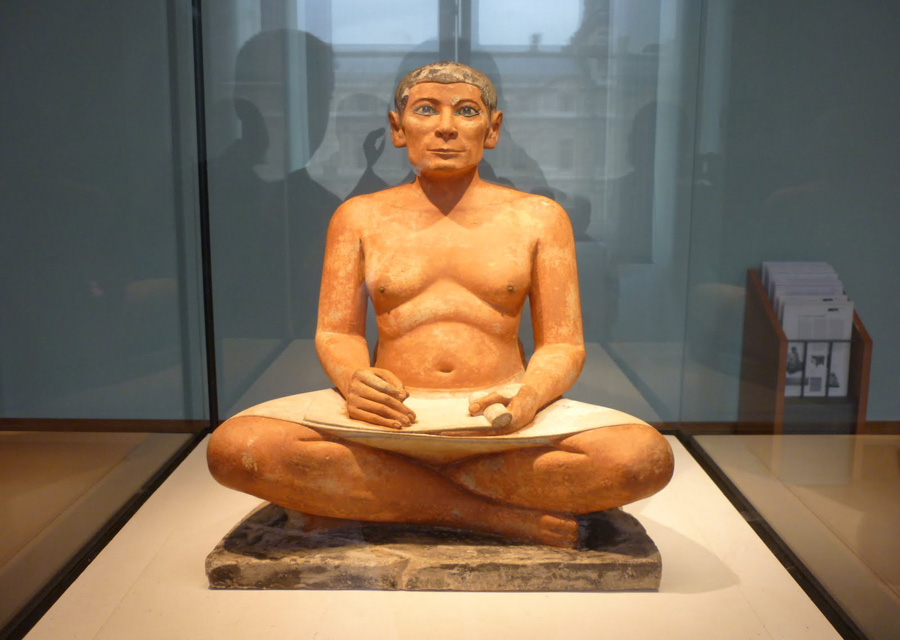

THE SEATED SCRIBE

Writing, symbolized

4th or 5th dynasty (2600 – 2350 B.C)

Found at Saqqara

Sully Wing—Room 635

This scribe sitting cross-legged is one of the most famous unknowns in art: we know neither his name, nor his titles, nor even the century in which he was sculpted. But the statue is in no way less admirable—or the sculptor’s dexterity less commendable. At the time, all they had as tools was a spike and a mallet! What is most striking is the treatment of the face, which is extremely meticulous, and involves an inlaying of the eyes and black paint strokes to draw the eyebrows. The hands, fingers and even nails are also sculpted with remarkable refinement. Its well-preserved antique polychromy gives the work its uniqueness, making it both warmer and more intriguing.

ANIMAL FIGURES

THE HIPPOPOTAMUS FIGURINE

On the side of the pharaohs

Middle Empire (around 2033 – 1710 B.C)

Sully Wing—Room 636

This Egyptian faience is absolutely remarkable, andnot only because of its peculiar blue colour. Its excellent state of conservation and its size (20,5 cm x 12,7 cm x 8,1 cm) make it a work to be admired without moderation in the ‘earthenware’ showcase on the first floor of the Sully wing. This type of sculpture is an object destined for the Afterlife in the Egyptian world, in 2,000 years B.C. Buried in the tombs of high Egyptian dignitaries, it symbolizes the rebirth of the dead—the Lotus flower on its hindquarters is an obvious illustration of this. However, the hippopotamus in the Louvre has no name. For the record, his twin, who is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is nicknamed William.

CORINTHIAN ARYBALLOS IN THE FORM OF AN OWL

Perfume Owl

Around 640 B.C – Greece, Corinth

Sully Wing—Room 655

This little owl, which is only 5 cm high, is nevertheless a technical and artistic jewel. It is more precisely an aryballe: a small perfume vase that was very popular in Greek Antiquity. This can be seen in the minute details such as the inner tank, the mouth and the openings in the base. Aesthetically, the perfect mastery of form, the line drawing, the black varnish and the apparent polychromy make the owl very expressive—and the object resolutely modern. A small firing accident scorched its wings, colouring the feathers—which must have used to be black—a beautiful red. Definitely a small perfume vase…really nice!

A YOUNG TIGER PLAYING WITH ITS MOTHER

Wild Scene

Sully Wing—Room 30

If Delacroix is mainly known for his historical, huge and epic paintings—such as his Liberty Leading the People—he is much less known for his paintings of landscapes and animals. Yet it is in these fields that his production was the most important. And it so happens that this painting of two tigers is quite representative of the feline paintings. The artist spent hours observing them in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, which is why an extensive attention to anatomy and colour is found at the heart of the artist’s work, which crosses here the line between painting and drawing. The languid pause of the two tigers, along with the tortured colours symbolize Delacroix’s art wonderfully, and remind visitors that he was what French poet Baudelaire called ‘the most original painter of ancient and modern times.’