Spotlight on traditional dials

Not all watch enthusiasts know this, but dials are one of the watch components that require the most manual work before their assembly. Here is a summary of what you need to know about them, in order to better understand their importance and to avoid using the wrong terms to describe them.

The dial is the face of a timepiece, and reflects its owner’s values. Its development requires great care since the aesthetic balance of the dial also determines the appreciation of the timepiece. Over the years, artists who work with watchmakers have developed many techniques to increase their perceived value. They adapted those techniques according to the period and trend. Now that many new brands have emerged, so has the need for them to distinguish themselves. Dials are now essential to the design process of all new watch products.

The enamel in detail

The brands that are the most interested in preserving the Métiers d’Arts produce enamel dials like those from the 16th century onwards. Enamel dials use a simple metal disk, usually in brass, copper or occasionally gold. The disk is coated in several layers of high-temperature soft glass then fired at a temperature of 500°C to 800°C. Craftsmen then apply markers on that baseplate, which is usually white and opaque but also ranges from red to black. Artists can also paint various patterns on the plate. In order to stabilise the colours, the baseplate undergoes firing each step of the process. Finally, to give these Grand Feu enamel disks a gleaming finish and guarantee they retain their shine and colours, they are covered with a transparent flux called a couverture.

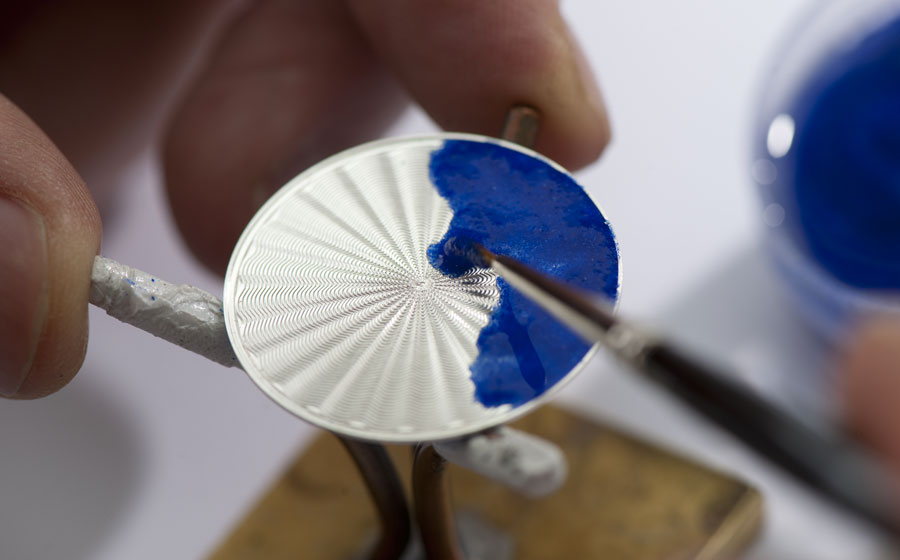

But there are many other types of enamel dials. First, those known as flinqué dials. Their surface is machine-engraved, hand-engraved or even stamped, then covered with a transparent or translucent enamel.

Professionals often mix up champlevé enamels and cloisonné enamels. For champlevé dials, artists etch into the baseplate according to a predetermined design. The resulting cavities are then filled with vitreous enamel.

For cloisonné dials, artisans apply strips of metal onto the disk to create separate areas in which they then put crystals of hot vitrifying minerals. They fire the disk several times throughout the process. Then, it is delicately lapped in order to get a completely flat and polished surface. Some Maisons sometimes lay a couverture on the dials to increase their brightness.

The very rare and fragile plique-à-jour enamel dial is obtained by dissolving the back of a cloisonné enamel.

Be careful with the terminology that has been used in watchmaking during the last few years. Indeed, some careless Maisons try to “outsmart” their competitors by offering cheap dials made with cold enamel. In other words, dials easily produced in large quantities from synthetic lacquers that polymerise in the air.

Classic decoration

Some dials display a surface covered with repetitive geometric patterns. In some rare cases, craftsmen make these decorations by hand, with a chisel. During the 18th century, and even more at the beginning of the 19th century, guilloché work became common for both dials and cases. The development of a new machine indeed allowed the semi-automatisation of the engraving process. Only a few brands still perform these surface treatments with specific machines. Now, it is much quicker and less expensive to achieve them through stamping, with digitally controlled milling machines or even specialised lasers.

The process of covering the decorations in hot enamel is called flinquage. The process of painting or lacquering very thin engraving obtained through a circular surface treatment is called azurage.

Sun-brushed dials display lines that start from the center of the dial. They are sunbrushed either by directly working the metal or by delicately levelling the varnish that protects the painting or the silvering of the dial.

Dial makers refer to in-round manual or mechanical engraving as ramolayé. This process is usually conducted on natural materials such as bone, ivory or mother-of-pearl.

Many dials are now made through painting or lacquering. Artisans spray highly-pigmented paint or use new generation printers on the baseplate. They usually fire it in the oven to stabilise the layers of paint before they decorate it with various elements.

Other dials display silver, gold, copper or rhodium-plated surfaces. Brands mostly use electroforming, a process of layering the baseplate in metal. They frequently use PVD, a technique of physical vapor deposition. Please note that some dials are directly crafted in 18-carat gold or rhodium-plated silver 950. The metal is stabilised with electroforming to prevent oxidisation in the air.

In order to apply the logo, brand name, railway track scale, sometimes Arabic or Roman numerals and special markers, brands often use pad printing with a cone in gelatine. After that, many dials are coated in an either cellulosic or epoxy protective varnish professionally referred to as “Zapon”.

For some dials, craftsmen pierce small holes into the surface of the plate to insert the base of the metal markers. They sometimes set or fill the markers with non-radioactive, luminescent material. Then, an expert rivets the small pieces, placed one by one by hand, on the back of the plate with a tool. These are dials with applied markers.

Sometimes, these markers are not riveted but glued on by machines in a single operation. This treatment, the décalque en relief, is often used on mid-range watches. But sometimes, the best models of fine watchmaking are also equipped with this kind of dial.